The Tall Sofa at IKEA

How shopping for a sofa taught me the Freudian theory of Rationalisation

This is an AI-assisted English translation. The original version is in Telugu

My mother and I accompanied my aunt to IKEA to help her buy furniture. You know how IKEA is—carnival! We were walking around, looking at different sofas. Some were too deep, so we rejected them. Some didn’t have nice colors. One by one, we ruled them out for various reasons.

Then, everyone thought hard and settled on one key criterion:

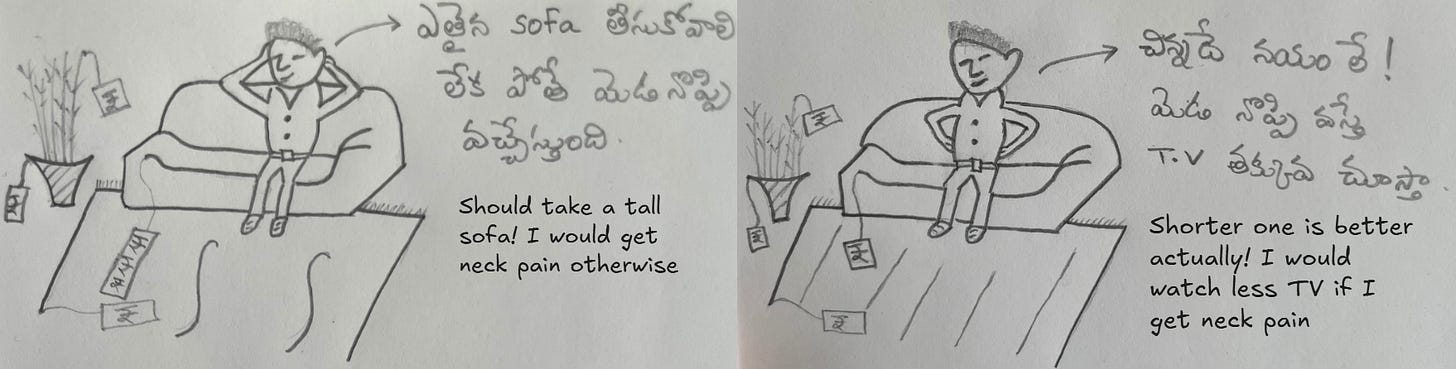

“You spend a lot of time in front of the TV, right? Choose a high-back sofa with a headrest. Otherwise, you’ll get neck pain,” my mom told my aunt. So we ruled out another small sofa.

We walked further through the furniture section. Our legs started to ache, and we were getting tired. We still hadn’t found a high-back sofa that we liked. Finally, we found a sofa that checked all the boxes—except it didn’t have a high back.

“If your neck starts to hurt, you won’t watch too much TV. This is better,” my mom said.

I was shocked.

“How can you argue both sides, Mom?” I asked.

She just laughed and moved on to buying the rest of the furniture.

When I got home and thought about the incident, a lot of things started making sense. It reminded me of the story of the fox and the grapes from childhood. We didn’t get the sofa we originally wanted, so we convinced ourselves that the one we bought was what we actually needed.

And it’s not just with shopping. We do this in all areas of life, don’t we?

Didn’t get that promotion you were aiming for? We tell ourselves, “It’s probably for the best. If I had gotten it, I might have suffered in the new role.”

Didn’t end up marrying the person you dreamed of? We compare them with some cruel or problematic spouses and conclude, “The one I ended up with is much better.”

This isn’t wrong. We don’t always get what we want, and we can’t let ourselves drown in sorrow. So we tell ourselves these stories and make peace with the present. If humans didn’t have this ability, we probably would have been wiped out long ago from the weight of our regrets.

But that doesn’t mean it’s something to glorify either. It’s just a habit. The downside is, we not only compromise on what we initially wanted—we start convincing ourselves we never wanted it in the first place. That’s harmless when it comes to buying a sofa, but in life, if we keep rationalizing everything, we risk forgetting what we truly want deep down.

The psychological term for this, coined by Sigmund Freud, is Rationalization. We can’t completely rid ourselves of this habit—like I said, it’s often useful in the short term. But we should learn to manage it. Otherwise, we end up hiding our deepest desires even from ourselves. And someday, that mask falls off, and we realize we’ve been living the very life we once swore we didn’t want. That realization can be devastating.

So how do we keep this habit in check? I don’t fully know. Depending on its intensity, we might need the help of a psychologist. But my little sofa incident taught me a lesson: If we had written down clearly what we were looking for in a sofa—along with the reasons—before going to IKEA, maybe we wouldn’t have let this habit take over. Even if we had eventually chosen a different sofa, we’d have known why, and we wouldn’t have deceived ourselves.

Similarly, writing down what we truly want—clearly and with reasons—in a journal can help. If we don’t get what we want, our brain will do its tricks to ease the pain. In those moments, our journal can help us stay honest with ourselves and avoid self-deception.